Russia and Ecology (part 2): What does the public think?

In part 1 we've covered the state position to economy. What is the stand of the public?

While Russia's military capabilities have long been a matter of international concern, the country's climate policy, or lack thereof, should be understood as an issue of equal significance. Russia's climate policy has the potential to inflict even more devastating consequences on the world than its military threat. The vast expanse of Russia's territory, combined with its poor climate policy decisions, creates an enormous global impact that is hard to ignore.

Severly polluted river Ambarnaja near city or Norilsk, photo by Norilsk Nickel

As a petrostate with a substantial influence on global environmental policies, Russia holds the power to significantly shape the course of climate action worldwide. Moreover, Russia's stance on climate change can directly impede the green transition in Europe and hinder global efforts to combat climate change.

Therefore, understanding and engaging with Russia's climate policy is essential for anyone concerned about the planet's environmental future and the pursuit of a sustainable, resilient world.

Russia is among the 20 countries with the largest developed oil and gas reserves. It is also among the nine countries responsible for 90% of global coal production. Furthermore, Russia plans to increase its gas and oil production by above 5% by 2030. The country is currently the fourth largest greenhouse gas emitter behind China, the US, and India. In addition, it is the world’s third-highest carbon emitter in history, responsible for some 7% of global cumulative CO2.

Climate change is undeniably a global issue, transcending national boundaries and affecting every corner of the Earth. However, the Russian government views climate change not as a universal challenge, but rather as individual issues that each nation should address independently. Moscow prioritises the preservation of its national sovereignty over concerns like deforestation in the Amazon or the rising sea levels affecting Pacific island nations.

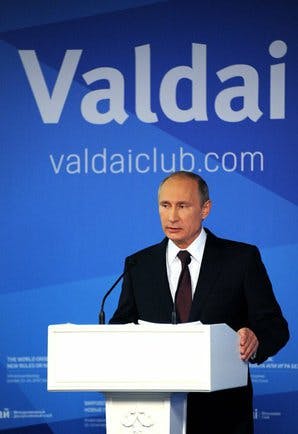

Vladimir Putin giving a speech at the Valdai Club gallery in October 2014

2020 report emphasises two aspects of sovereignty to climate policy:

Consequently, during international climate negotiations, Russia strongly opposes efforts to establish compulsory targets and instead adopts a minimalist stance by limiting its area of responsibility to adhering to its contractual obligations.

Throughout three decades, Russia's climate policy has been pragmatic in nature, neglecting international climate agreements to serve “higher priority” goals. These include:

This image was generated by AI

Moscow's stance has remained nearly unaltered, extending from the 1992 Rio Climate Conference when the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was established, through the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, to the 2015 Paris Agreement.

The process of ratifying these agreements reflects Moscow's minimal commitment. Russia took two years to ratify the UNFCCC, seven years for the Kyoto Protocol, and four years for the Paris Agreement. Delays, at least in some cases, were not primarily due to substantive issues but rather stemmed from the Kremlin's attempt to leverage ratification for other strategic objectives.

The approach towards the Kyoto Protocol exemplifies a distinctly pragmatic mindset. Initially, while the United States was a signatory to the Protocol, Russia aimed to profit by selling surplus emissions allowances to the world's largest and most industrialised economy. Following the U.S. withdrawal from the Kyoto Protocol in 2001, Russia's interests shifted from purely financial to geo-economic. Recognising that the Kyoto Protocol could only enter into force upon Russian ratification, Moscow effectively turned this ratification into a condition for its entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO).

Moscow's pragmatic approach was less conspicuous in its response to the Paris Agreement, which lacked financial or geo-economic incentives that could facilitate Russia's ratification. Nevertheless, as in the past, Russia's policy was influenced more by a calculated assessment of short-term costs and benefits than by concerns about global warming. At a time when the United States' moral and political standing was historically low, arguments in favour of Russia's alignment with the international consensus grew more compelling. Ratification bolstered Russia's reputation as a responsible member of the global community without imposing significant obligations. From Moscow's perspective, it appeared to be a situation with mutually beneficial outcomes.

Polar bears feed at a garbage dump near the village of Belushya Guba, on the remote Novaya Zemlya islands in northern Russia in October 2018. This is a military area where bears have began to enter in search of food due to Arctic ice melting. Photo: Alexander Grir / AFP

Moscow's continuing insistence on maintaining the Kyoto Protocol 1990 benchmark as the yardstick for future reductions in Russian emissions renders it challenging to commit to achieving a 25-30 percent reduction by 2030. Currently, Russia's carbon dioxide emissions are notably lower than during the Soviet period (in 2017, they were 32% lower than in 1990). This enables the Russian government to pursue ambitious plans for expanding fossil fuel production while still meeting its contractual obligations.

Similar to its approach with the Kyoto Protocol, Moscow's agenda concerning the Paris Agreement is not primarily oriented towards environmental objectives, such as mitigating global warming, improving air quality, or preserving permafrost. Their paramount concern is to ensure that the pursuit of global climate goals does not impede Russian national interests as defined by the ruling elite.

As Deputy Minister of Energy Anastasia Bondarenko explicitly stated:

The implementation of international climate policy should not encroach on the interests of energy-producing countries

Anastasia Bondarenko, Deputy Minister of Energy

Therefore, it is unsurprising that the result of this perspective is not a proactive climate policy but rather a reactive, opportunistic, and self-centred approach.

National Climate Policy formation is significantly influenced by specific political figures, most notably, President Vladimir Putin. This does not imply that he possesses absolute authority or is directly involved in every phase of decision-making. Nevertheless, his sceptical stance regarding the anthropogenic aspect of climate change has played a pivotal role in shaping Russia's policies over the past two decades. Additionally, Putin represents an elite segment that tends to regard the climate emergency as a mere “liberal whim”, perceiving it as a far lesser threat than, for instance, economic recession, American “hegemony”, or liberal values. However, a change of rhetoric was noticed in 2022 when Putin already named climate change as the greatest challenges facing humanity.

At a press conference in 2019, Putin claimed that “no one knows the true cause of climate change”, adding that calculating how humanity affects global climate change “is very difficult, if not impossible”. However, as early as 2013, the United Nations' Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) conveyed in its fifth assessment report that it was "extremely likely" that over half of the observed increase in global average surface temperature from 1951 to 2010 resulted from human activities, indicating a 95% to 100% probability. In its 2021 report, the IPCC featured a dedicated chapter addressing human influence on the climate system, unequivocally stating that human activity has indisputably warmed the global climate system since pre-industrial times. Professor Ed Hawkins, an IPCC author, emphasised during a press briefing:

…It is unequivocal and indisputable that humans are warming the planet… And every government agreed to that.

Professor Ed Hawkins, IPCC author

Today, the origins of the current climate change are not under dispute anymore; the scientific consensus is that humans are responsible for 100% of current warming.

Moreover, Russian climate policy is shaped by the influence of powerful private interests, with the most significant among them being the energy sector, which serves as the cornerstone of the national economy. In 2018, hydrocarbons contributed to 46% of national budget revenues, 65% of total export earnings, and 25% of Russia's gross domestic product (GDP). These figures, which are impressive in their own right, translate into substantial political clout for leading energy corporations. Their sway extends across various areas of governmental control, particularly in hindering any progress toward a post-industrial and post-carbon economy. The energy companies' agenda closely aligns with the broader strategic aspirations of Putin's regime.

Among the influential groups are the Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs (RSPP) and the agricultural sector. RSPP's influence became apparent during the formulation of the Russian government's plan for adapting to climate change in late 2019. Earlier versions of the plan proposed the introduction of a carbon tax and penalties for companies exceeding emission limits. However, even these relatively modest measures were subsequently scrapped in favour of a toothless five-year "climate audit." The Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs justified their position by stating:

We must maximise and continually increase sales of gas, oil, and coal while there is still a buyer.

Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs

A similar disposition is observed in the agricultural sector, which is not inclined to modify intensive farming methods to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Instead, their primary focus is on maximising production and exports.

Moscow prioritises the production of fossil fuels due to its belief in this industry's strength. It lacks the will to develop a post-industrial, high-tech, and low-carbon economy capable of replacing the current carbon-intensive industrial model.

In part 1 we've covered the state position to economy. What is the stand of the public?

Short biography of the freedom that never happened.

In Russia, stark regional disparities exist, shaped by history, geography, and economics. From thriving urban centres to struggling rural regions, these inequalities demand a comprehensive approach. How did you imagine Russia?

Our media platform would not exist without an international team of volunteers. Do you want to become one? Here's the list of currently opened positions:

Is there any other way you would like to contribute? Let us know:

We talk about the current problems of Russia and of its people, standing against the war and for democracy. We strive to make our content as accessible as possible to the European audience.

Do you want to cooperate on content made by the Russian standing against the war?

We want to make people of Russia, who stand for peace and democracy, heard. We publish their stories and interview them in Ask a Russian project.

Are you a person of Russia or know someone who would like to share their story? Please contact us. Your experience will help people understand how Russia works.

We can publish your experience anonymously.

Our project is ran by international volunteers - not a single member of the team is paid in any way. The project, however, has running costs: hosting, domains, subscription to paid online services (such as Midjourney or Fillout.com) and advertising.

Our transparent bank account is 2702660360/2010, registered at Fio Banka (Czech republic). You can either send us money directly, or scan one of the QR codes bellow in your banking app:

Note: The QR codes work only when you scan them directly from your banking app.

Russia started the war against Ukraine. This war is happening from 2014. It has only intensified on February 24th 2022. Milions of Ukrainians are suffering. The perpetrators of this must be brought to justice for their crimes.

Russian regime tries to silence its liberal voices. Russian people against the war exist - and the Russian regime tries its best to silence them. We want to prevent that and make their voices heard.

Connection is crucial. The Russian liberal initiatives are hard to read for European public at times. The legal, social and historical context of Russia is not always clear. We want to share information, build bridges and connect the liberal Russia with The West.

We believe in dialogue, not isolation. The oppositional powers in Russia will not be able to change anything without the support of the democratic world. We also believe that the dialogue should go both ways.

The choice is yours. We understand the anger for the Russian crimes. It is up to you whether you want to listen to the Russian people standing against this.